SPECCHIO ETRUSCO: Evan e Itinthni

ANTICHI POPOLI ha inserito le Didattiche su Cosmesi e Igiene tra le ricostruzioni storiche di living history.

Non potevamo esimerci dal mostrare uno specchio etrusco. Ciò che distingue gli specchi etruschi dai greci sono principalmente i decori incisi sul retro. Negli esemplari greci la decorazione, incisa, è sovente limitata al manico e alla targhetta. Lo specchio etrusco , generalmente in bronzo, è tipicamente a disco ed ha una parte liscia, riflettente, leggermente convessa che amplia e deforma un poco l’immagine riflessa. La parte decorata sul retro risulta pertanto leggermente concava, specie sui bordi, il che lo rende utile anche per evitare danni alla decorazione incisa.

La parte decorata sul retro risulta pertanto leggermente concava, specie sui bordi, il che lo rende utile anche per evitare danni alla decorazione incisa.

Specchi col retro decorato erano in uso anche in Gallia tuttavia la decorazione era geometrica a motivi curvilinei: spesso era usato il tema celtico del triskel.

Lo specchio fa spesso parte del corredo funebre femminile perché era un oggetto tipico della toilette della donna Etrusca, famosa nel mondo antico per la cura del corpo, il trucco, la bellezza. Le scene rappresentate nelle decorazioni incise sugli specchi etruschi sono quasi sempre scene mitologiche greche appositamente selezionate per la loro affinità col mondo muliebre.

Lo specchio fa spesso parte del corredo funebre femminile perché era un oggetto tipico della toilette della donna Etrusca, famosa nel mondo antico per la cura del corpo, il trucco, la bellezza. Le scene rappresentate nelle decorazioni incise sugli specchi etruschi sono quasi sempre scene mitologiche greche appositamente selezionate per la loro affinità col mondo muliebre.

Molti specchi in commercio sono però di tipo Greco o Romano. Gli specchi in bronzo Romani sono più una produzione industrializzata che artistica: sono solitamente di forma quadrata, già apparsa negli ultimi tempi della cultura etrusca, e con pochi decori: statuette di sostegno o teche a rilievo.

È stato complicato trovarne uno veramente etrusco. È stato il nostro etruscologo Alessio Muzzoni a verificare che lo specchio recasse incisioni in etrusco . Il mito rappresentato nell’incisione è molto noto cionondimeno è stato complicato risalire allo specchio che la replica riproduceva, anche per un errata catalogazione dell’originale, ma infine Alessio Muzzoni è riuscito a recuperare tutto. Si tratta della replica di uno Specchio di bronzo graffito di provenienza ignota, che appartiene allo Staatlische Museum di Berlino, 3386 (Fr. 70). Seconda metà del IV secolo a.C. L’originale risulta mal conservato purtroppo.

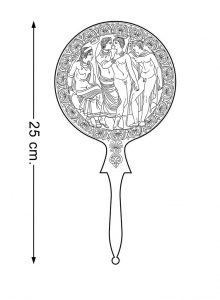

Specchio di bronzo graffito. Provenienza ignota. Berlino, Staatlische Museum 3386 (Fr. 70). Seconda metà del IV secolo a.C.

Lo specchio in bronzo, di diametro 18,5 cm, è alto 21,5 cm è stato acquisito nel 1859 da precedente proprietario: Coll. Gerhard; Professore archeologo Eduard Gerhard (1795-1867).

Sul retro la decorazione incisa presenta una scena mitologica: Al centro Eos, dea dell’aurora (iscrizione Evan), stante, seminuda, abbraccia il compagno Tithonos (iscrizione: Itinthni) stante, nudo. Assistono alla scena: a dx. Tvami stante, forse appoggiato con la destra a una lancia, nudo con clamide sulle spalle, calzato; a sx. Thetis (Iscrizione: Thethis) seduta seminuda. Se è verosimile identificare nella coppia di amanti Eos e Tithonos, le due figure laterali avranno un ruolo di complemento alla scena:

Disegno dello specchio di Berlino, Staatlische Museum 3386 (Fr. 70). Seconda metà del IV secolo a.C.

Thetis può essere un richiamo al mare oltre cui è portato il giovane rapito, o può svolgere un ruolo affine a quello di personaggio della cerchia di Turan; Tvami può essere interpretato, sulla base di simili scene di seduzione, come un compagno di Tithonos. Tithonos è un antico dio della luce e come tale il consueto compagno e complemento di Eos.

Nel processo di unificazione delle storie mitiche attraverso regolari genealogie, Tithonos diviene un principe troiano figlio di Laomedonte e fratello di Priamo, uomo di mirabile avvenenza, fu rapito da Eos e portato in Etiopia, dove ebbero i due figli: Memnone e Emazione. Eos chiese a Zeus di donargli l’immortalità, dimenticando però di richiedere anche l’eterna giovinezza, così Tithonos visse per sempre ma lo fece invecchiando e così, sempre più vecchio e privo di forze e con solo la possibilità di parlare con una voce acuta, Eos chiese ed ottenne che fosse mutato in una cicala.

Nel processo di unificazione delle storie mitiche attraverso regolari genealogie, Tithonos diviene un principe troiano figlio di Laomedonte e fratello di Priamo, uomo di mirabile avvenenza, fu rapito da Eos e portato in Etiopia, dove ebbero i due figli: Memnone e Emazione. Eos chiese a Zeus di donargli l’immortalità, dimenticando però di richiedere anche l’eterna giovinezza, così Tithonos visse per sempre ma lo fece invecchiando e così, sempre più vecchio e privo di forze e con solo la possibilità di parlare con una voce acuta, Eos chiese ed ottenne che fosse mutato in una cicala.

Titone (Tinthu, Tinthun, Itinthni ) ed Eos ( Thesan, Evan) erano spesso raffigurati sul posteriore degli specchi a mano ed in bronzo degli Etruschi. Uno di questi è conservato nei Musei Vaticani.

ANTICHI POPOLI has included the Didactics on Cosmetics and Hygiene among the historical reconstructions of living history.

We could not avoid showing an Etruscan mirror. What distinguishes the Etruscan mirrors from the Greeks is mainly the decorations engraved on the back. In Greek specimens, the decoration, engraved, is often limited to the handle and the plate. The Etruscan mirror, generally in bronze, is typically disc-shaped and has a smooth, reflective, slightly convex part that widens and slightly deforms the reflected image. The part decorated on the back is therefore slightly concave, especially on the edges, which makes it useful also to avoid damage to the engraved decoration.

Mirrors with a decorated back were also used in Gaul; however, the decoration was geometric with curvilinear motifs: the Celtic triskel theme was often used.

The mirror is often part of the female funeral kit because it was a typical object of the Etruscan woman’s toilet, famous in the ancient world for body care, make-up, beauty. The scenes represented in the decorations engraved on the Etruscan mirrors are almost always Greek mythological scenes specially selected for their affinity with the world of women.

Many mirrors on the market, however, are of the Greek or Roman type. Roman bronze mirrors are more an industrialized than an artistic production: they are usually square in shape, already appeared in the last times of the Etruscan culture, and with few decorations: support statuettes or relief cases.

It was difficult to find a truly Etruscan one. It was our etruscologist Alessio Muzzoni to verify that the mirror had etruscan engravings. The myth represented in the engraving is very well known, however, it was difficult to trace the mirror that the replica reproduced, also due to incorrect cataloging of the original, but finally Alessio Muzzoni managed to recover everything. It is the replica of a graffiti bronze mirror of unknown origin, which belongs to the Staatlische Museum in Berlin, 3386 (Fr. 70). Second half of the 4th century BC The original is unfortunately poorly preserved.

The bronze mirror, 18.5 cm in diameter, 21.5 cm high was acquired in 1859 by the previous owner: Coll. Gerhard; Professor archaeologist Eduard Gerhard (1795-1867).

On the back the engraved decoration presents a mythological scene: In the center Eos, goddess of the aurora (inscription Evan), standing, half-naked, embraces Comrade Tithonos (inscription: Itinthni) standing, naked. Attend the scene: right. Tvami standing, perhaps leaning with his right hand on a spear, naked with chlamys on his shoulders, shod; left. Thetis (Inscription: Thethis) sitting half-naked. If it is likely to identify in the pair of lovers Eos and Tithonos, the two lateral figures will have a role of complement to the scene: Thetis can be a call to the sea beyond which the kidnapped young man is brought, or he can play a role similar to that of a character of the circle of Turan; Tvami can be interpreted, on the basis of similar seduction scenes, as a companion of Tithonos. Tithonos is an ancient god of light and as such the usual companion and complement of Eos. In the process of unification of the mythical stories through regular genealogies, Tithonos becomes a Trojan prince son of Laomedonte and brother of Priam, a man of admirable attractiveness, was kidnapped by Eos and taken to Ethiopia, where they had their two children: Memnon and Emazione. Eos asked Zeus to give him immortality, forgetting to ask for eternal youth too, so Tithonos lived forever but he did it getting old and so, getting older and without strength and with only the possibility to speak with a high-pitched voice, Eos asked and obtained that it be changed into a cicada.

Titone (Tinthu, Tinthun, Itinthni) and Eos (Thesan, Evan) were often depicted on the back of the hand and bronze mirrors of the Etruscans. One of these is kept in the Vatican Museums.